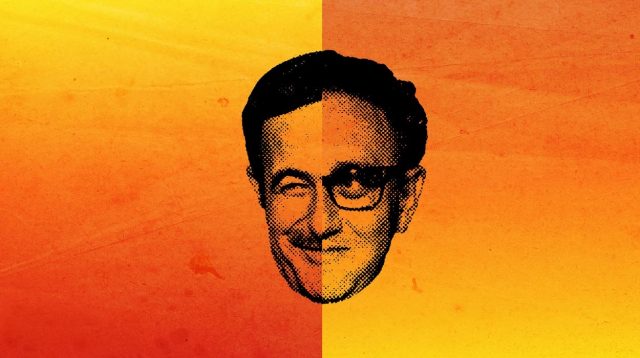

December 7 was the anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 and of the birth thirteen years earlier of Noam Chomsky. Pearl Harbor led to American global dominance at the same time as Chomsky’s insights into the nature of language were beginning to have an impact on linguistic theory, philosophy and psychology. Chomsky is also an outspoken critic of his country’s foreign policy. Expanding his critique of B. F. Skinner’s and W. V. O. Quine’s behaviourist determinism to the political realm, he has developed a libertarian and socialist vision of free will, opposition to concentrations of private and state power, and resistance to the abuse of power at home and abroad.

Throughout his adult life, from his moral opposition to America’s invasion of Vietnam to his country’s more recent adventures in Afghanistan and Iraq, Chomsky has argued that the US behaves much as its Spanish, British and French imperial predecessors once did. Moreover, he notes, the US has employed the same moral language to cover what appear to be global atrocities. Like Marlow in Heart of Darkness, he believes, “The conquest of the earth, which mostly means the taking it away from those who have a different complexion or slightly flatter noses than ourselves, is not a pretty thing when you look into it too much”. Those Chomsky has consistently condemned must feel that he has looked into it too damned much…

Continue reading →